Manufactured Deliciousness: Why you can’t stop overeating

(plus 3 strategies to get control)

You know the feeling: One salty crunch turns into 100, and suddenly you’re licking the cheese dust and wondering: What’s wrong with me?

Actually, it’s normal to feel like you can’t stop overeating certain things. Today’s hyperpalatable food is creating a modern-day food crisis—one that’s leaving us feeling sick, out of control, and constantly craving more.

Here’s how it works, plus 3 ways to overcome it.

It’s happened to us all.

After a frenzy of lustful grabbing and furious crunching, we find ourselves at the bottom of a jumbo bag of crisps.

“How did that happen?” we ask fuzzily.

“What’s wrong with me? Why can’t I stop?”

But, before going into full-fledged self-loathing mode, consider this.

Processed foods are scientifically engineered to be irresistible and easy to gobble up in large quantities. If you can’t stop, the crisps are doing their job.

(In fact, someone at Frito-Lay probably got a promotion for that recipe.)

That’s why, in this article, we’ll explain exactly how junk food is designed to make us respond with compulsive, manic, gotta-have-more snack sessions.

Even better, we’ll arm you with three useful strategies for examining your relationship with processed food and taking control of overeating.

Because, if you feel out of control around certain foods, you’re not crazy.

Even healthy eaters feel out of control around food sometimes. Even if we value nutrition and want to take care of ourselves, some foods can make us feel… kinda possessed.

Know what I mean?

You show up to a potluck with quinoa salad goals and find yourself inhaling a plate of crisps, cookies, and some chocolate-peanut-butter-marshmallow thing that some devil, um friend, made.

You reach into the freezer to have one spoonful of ice cream and suddenly you’re mining the caramel swirl, then the nut clusters, then the brownie chunks, and then… your spoon scrapes the bottom.

You just want a bite of your friend’s chips, but you find yourself elbowing her out of the way so you can steal all the chips, plus the burger too.

Even with the best intentions, the pull of certain foods is so strong that it can leave us feeling powerless.

If you’ve felt this, you’re not alone (and you’re not broken).

Certain foods are actually designed to make us overeat.

If you’re overeating, it’s not because there’s something wrong with you or your willpower.

Here’s the truth: There’s a whole industry dedicated to creating food that’s hyperpalatable—food that’s so tasty it’s nearly irresistible.

Your body and brain are responding exactly as they’re supposed to. It’s supposed to feel almost unnatural to stop eating these foods!

But we’re not talking about food like celery sticks, whole brown rice, or baked salmon filets.

(How often do you hear yourself say, “I ate sooo much steamed asparagus! I just couldn’t stop myself!” That’s right. You’ve never heard yourself say that.)

We’re talking about processed foods.

Processed foods are foods that have been modified from their original, whole-food form in order to change their flavour, texture, or shelf-life. Often, they’re altered so that they hit as many pleasure centres as possible—from our brains to our mouths to our bellies.

Processed foods are highly cravable, immediately gratifying, fun to eat, and easy to over-consume quickly (and often cheaply).

Processed foods will also look and feel different from their whole food counterparts, depending on the degree that they’re processed.

Let’s take corn as an example.

Boiled and eaten off the cob it’s pale yellow, kinda fibrous, but chewy and delicious.

Corn that’s a bit processed—ground into a meal and shaped into a flat disk—turns into a soft corn tortilla. A tortilla has a nice corny flavour and a soft, pliable texture that makes it easy to eat and digest.

But what if you ultra-process that corn? You remove all the fibre, isolate the starch, and then use that starch to make little ring-shaped crisps, which are fried and dusted with sweet and salty barbecue powder. They’re freaking delicious.

That corn on the cob is yummy. But those corn-derived ring crisps? They’re… well they’re gone because someone ate them all.

Let’s take an even deeper look

The food industry has a variety of processing methods and ingredient additives they use to make food extra tasty and easy to consume…. and over-consume.

Here are a few examples:

Extrusion

Grains are processed into a slurry and pass through a machine called an extruder. With the help of high heat and pressure, whole, raw grains get transformed into airy, crispy, easy-to-digest shapes like cereals, crackers, and other crunchy foods with uniform shapes.

In addition to changing texture and digestibility, the extrusion process also destroys certain nutrients and enzymes, denatures proteins, and changes the starch composition of a grain. This lowers the nutrition and increases the glycemic index of the product.

Emulsifiers

Used to improve the “mouth feel” of a product, emulsifiers smooth out and thicken texture, creating a rich, luxurious feel. Although there are natural emulsifiers, like egg yolk, the food industry often uses chemical emulsifiers like Polysorbate-80, sodium phosphate, and carboxymethylcellulose.

Emulsifiers are often found in creamy treats like ice cream products and processed dairy foods like flavoured yogurts or neon orange cheese spreads.

Flavour enhancers

Flavour additives like artificial flavouring agents or monosodium glutamate (MSG) allow food manufacturers to amplify taste without adding whole-food ingredients like fruits, vegetables, or spices. This is useful because artificial flavouring agents are cheap and won’t change a product’s texture.

Colouring agents

Colour strongly affects how appealing we perceive a food to be. No one wants to eat grey crackers; add a toasty golden hue and suddenly that cracker is a lot more appealing. Colouring agents, like Yellow #5 (tartrazine) and Red #40 (allura red), are added purely for the look of food—they don’t add nutrition.

Recently, many large food corporations have been switching to natural foods dyes, like beet powder or turmeric, to colour their food products after some correlations emerged linking artificial colouring agents to behavioural problems in children.

Oil hydrogenation

Natural fats eventually go rancid, changing their flavour and texture. In order to render fats more stable, hydrogen atoms are added to fats (usually vegetable oils) so they are less vulnerable to oxidation.

Food manufacturers use hydrogenated oils because it means their products can stay on the shelves for longer without changing flavour or texture. However, the consumption of hydrogenated fats, or trans fats, has been linked to increased rates of heart disease.

How processed foods trick us into eating more than we meant to.

There are four sneaky ways processed food can make you overeat. Often, we’re not even aware of how much these factors affect us.

That’s why, awareness = power.

1. Marketing convinces us that processed foods are “healthy”.

Processed foods come in packages with bright colors, cartoon characters, celebrity endorsements, and powerful words that triggers all kinds of positive associations.

Take, for example, “health halo” foods.

“Health halo” foods are processed foods that contain health buzzwords like organic, vegan, and gluten-free on their label to create an illusion, or halo, of health around them.

Companies come out with organic versions of their boxed macaroni and cheese, gluten-free versions of their glazed pastries, and vegan versions of their icing-filled cookies.

You’ll see crisps “prepared with avocado oil,” sugary cereal “made with flaxseeds,” or creamy dip with “real spinach.”

The nutrient content of those foods isn’t particularly impressive, but the addition of nutrition buzzwords and trendy ingredients make us perceive them as healthier.

Marketers also choose words that relate more broadly to self-care.

Ever notice how many processed food slogans sound like this?

“Have a break.”

“Take some time for yourself.”

“You deserve it.”

Words like “break” and “deserve” distract us from our physical sensations and tap into our feelings—a place where we just want to be understood, supported, soothed, and perhaps just escape for a moment.

Health buzzwords and emotional appeals can make us perceive a food as “good for me”; it seems like a wise and caring choice to put them in our shopping carts, then in our mouths.

And if a food is “healthy” or “we deserve it,” we don’t feel so bad eating as much as we want.

2. Big portions make us think we’re getting a “good deal”.

People get mixed up about food and value.

We’re taught to save money and not waste food.

We’re taught to buy more for less.

Given the choice between a small juice for two dollars, and a fizzy drink with endless refills for the same price, the fizzy drink seems like better value.

What we don’t calculate into this equation is something I like to call the “health tax.”

The “health tax” is the toll you pay for eating low-nutrient, highly processed foods. If you eat them consistently over time, eventually you’ll pay the price with your health.

When companies use cheap, poor quality ingredients, they can sell bigger quantities without raising the price.

But what’s the deal?

Sure, you’ll save a quid in the short term, but you’ll pay the health tax—through poor health—in the long term.

3. Variety makes us hungrier.

Choice excites us.

Think of a self-serve frozen yogurt topping bar:

“Ooh! Sprinkles! And beer nuts! Oh, and they have those mini peanut butter cups! And granola clusters! Wait, are those crushed cookies?? And cheesecake chunks??! YES! Now on to the drizzles…”

Before you know it, there‘s a leaning tower of frozen dessert in front of you.

Or think of those “party mixes”—pretzels and crisps and cheesy puffs and barbeque rings—all in one bag! The fun never ends because there’s a variety of flavours and textures to amuse you forever!

When we have lots of variety, we have lots of appetite.

It’s hard to overeat tons of one thing, with one flavor, like apples.

How many apples can you eat before, frankly, you get bored?

Reduce the variety and you also reduce distraction from your body’s built-in self-regulating signals. When we’re not so giddy with choice and stimuli, we’re more likely to slow down, eat mindfully, and eat less.

4. Multiple flavors at once are irresistible.

If there’s a party in your mouth, you can guarantee that at least two out of three of the following guests will be there:

- Sugar

- Fat

- Salt

These three flavors—the sweetness of sugar, the luxurious mouthfeel of fat, and the sharp savory of salt—are favorites among those of us with mouths.

I never hear my clients say that they love eating spoonfuls of sugar or salt, or that they want to chug a bottle of oil.

However, when you combine these flavours, they become ultra delicious and hard-to-resist. This is called stimuli stacking—combining two or more flavours to create a hyperpalatable food.

For example:

- The satisfying combination of fat and salt, found in chips, crisps, nachos, cheesy things, etc.

- The comforting combination of fat and sugar, found in baked goods, fudge, ice cream, cookies, chocolate, etc.

- The irresistible combination of all three—heaven forbid you stumble on a combo of fat, salt, and sugar—a salted chocolate brownie, or salted caramel with candied nuts, or chips with ketchup!

Food manufacturers know: When it comes to encouraging people to overeat, two flavors are better than one.

In fact, when I spoke to an industry insider, a food scientist at a prominent processed food manufacturer, she revealed the specific “stimuli stacking” formula that the food industry uses to create hyperpalatable food.

They call it “The Big 5.”

Foods that fulfill “The Big 5” are:

- Calorie dense, usually high in sugar and/or fat.

- Intensely flavored—the food must deliver strong flavor hits.

- Immediately delicious, with a love-at-first taste experience.

- Easy to eat—no effortful chewing needed!

- “Melted” down easily—the food almost dissolves in your mouth, thus easy to eat quickly and overconsume.

When these five factors exist in one food, you get a product that’s practically irresistible.

In fact, foods developed by this company have to hit the big 5, or they’re not allowed to go to market.

When processed food manufacturers evaluate a prospective food product, the “irresistibility” (the extent to which a person can’t stop eating a food) is more important even than taste!

Just think about the ease of eating whole foods versus processed foods:

Whole foods require about 25 chews per mouthful, which means that you have to slow down. When you slow down, your satiety signals keep pace with your eating and have a chance to tell you when you’ve had enough. Which is probably why you’ve never overeaten Brussel sprouts (also because, farting).

Processed food manufacturers, on the other hand, aim for food products to be broken down in 10 chews or less per mouthful. That means the intense, flavorful, crazy-delicious experience is over quickly, and you’re left wanting more—ASAP.

Restaurants use these “ease of eating” tactics, too.

A major national chain uses this sci-fi-esque trick:

To make their signature chicken dish, each chicken breast is injected with a highly flavored sauce through hundreds of tiny needles. This results in a jacked-up chicken breast with intense flavor hits, but also tenderizes the chicken so it requires less chewing.

In other words, there’s a reason that restaurant chicken often goes down easier and just tastes better than the simple grilled chicken breast you make in your kitchen. Unless you have hundreds of tiny sauce-needles (weird), that chicken is hard to recreate at home.

This is why I rarely talk about willpower when my clients come to me struggling with overeating. If you’re relying on willpower to resist these foods, you’re fighting an uphill battle.

The solution isn’t more willpower. The solution is educating yourself about these foods, examining your own relationship with food, and employing strategies that put you in control.

Let’s take an even deeper look

Our love of certain flavors has very primitive roots.

So does our desire to load up on calories.

Once upon a time, food was not so abundant. Not only was food challenging to obtain—through effortful scavenging and hunting—but it was also not reliably safe.

That leaf over there? Yeah, that could be poison.

Those berries? They might give you the runs or make your throat close up.

Therefore, our ancient ancestors evolved some survival instincts along the way.

For example, sweet foods tend not to be poisonous. Therefore, we stored a preference for sweet, starchy foods in our brains to keep us safe.

Babies and children are particularly attracted to sweet foods, probably because their immature immune systems are less likely to recover from eating a poisonous plant, and their immature brains can’t tell the difference between dangerous bitter green (like hemlock) and safe bitter green (like kale).

Therefore, kids’ attraction to sweet (read: safe) foods is a built-in mechanism to prevent death by poisoning.

Fat is also a preferred nutrient, as it’s high-calorie and would be a jackpot for our often-threatened-by-starvation ancestors.

While most foods our ancestors ate would have been fibrous and low-calorie (roots, greens, lean meats), fat would have been a highly prized treat.

Imagine, as a primitive hunter-gatherer, stumbling on a macadamia nut tree. The yield from that tree might provide enough calories to feed your tribe for days!

As a result, we stored another preference in our brains: fatty, calorie-dense foods = yum / stock up!

Today, of course, we don’t have to run and dig and hike for nine hours to get our food. Instead, we can just roll up to the drive-thru window and order a combination of flavours we’re primed to love—maybe in the form of a milkshake and a cheeseburger—and enjoy it while sitting in our car.

Evolution’s gifts now work against us.

So, now you see why processed foods are so hard to control yourself around.

But what can actually you do about it?

Up next, some practical strategies to put you in the driver’s seat.

3 strategies to find your way back to a peaceful relationship with food.

It’s one thing to know in theory why certain foods are so easy to over-consume, but it’s even more valuable to discover for yourself how food processing, certain ingredient combinations, marketing, and even easy accessibility affect you and your food choices.

So, it’s time to get a little nerdy, try some experiments, and learn some strategies that will help you improve your relationship with food, get healthier, and just feel more sane.

1. Get curious about the foods you eat.

We’ve established that processed foods are designed to be easy to eat.

For a food to be “easy to eat”, it has to be:

- broken down easily (less chewing), and

- low volume (doesn’t take up much physical space).

So:

Less chewing + Low volume = More eating

Chewing takes time. The more we have to chew something, the longer it takes us to eat, giving our fullness signals a chance to catch up.

That feeling of “fullness” matters a lot too.

When you eat, your stomach expands. It’s partly through that sensation of pressure that your body knows you’ve had enough. Processed foods deliver a lot of calories without taking up much space, meaning you can eat a lot before you realize you’ve overdone it.

Experiment #1: Observe as you chew.

Yup, that’s right. I want you to count your chews.

Note: Don’t do this forever. I’m not trying to turn you into the weirdo who no one wants to sit next to at the lunch table. Just try it as an experiment to get some data about how you eat different foods.

First, eat a whole food—a vegetable, fruit, whole grain, lean protein, whatever—and count how many chews you take per mouthful. How long does it take to eat an entire portion of that food? How satiated do you feel afterward? Do you want to eat more?

Then, next time you eat something processed, count how many chews you take per mouthful. How long does it take to eat that serving of pasta, chips, or cookies? How satiated do you feel afterward? Do you want to eat more?

Make some comparisons and notice the differences. Contrast how long eating each of these foods takes you, how satiated you feel after eating each of them, and how much you want to keep eating.

How will you use that information to make food choices moving forward?

2. Notice the messages you’re getting about food.

Food manufacturers use creative marketing strategies to imply processed foods are healthy. And even if you know they’re not, they have other ways of getting you to buy them.

Here’s an example:

Ever notice that the produce section is the first area you pass through in supermarkets?

Supermarkets have found that if they put the produce section first, you’re more likely to purchase processed foods. This is probably because if you’ve already got your cart loaded with spinach, broccoli, and apples, perhaps you’ll feel better about picking up some ice cream, cookies, and crackers, before heading to the checkout line.

Let that sink in: The supermarkets we all shop in several times a month are designed to make you feel better about buying foods that could negatively impact your health goals.

The good news? Simply being aware of this trick can help you bypass it.

Experiment #2: Evaluate your pantry.

In this experiment, you’ll examine the foods you have in your home and the messages you’ve been given about them.

Note: Keep in mind that this is a mindful awareness activity. You’re not doing this to judge yourself or feel shame about the food choices you’ve made.

Look at your pantry with curious (and more informed) eyes.

- Step 1: Look for “health halo” foods. Do you have any? If so, why did you choose them? Was it the language used to describe it? Was it the packaging? A trendy “superfood” ingredient? Is it organic, gluten-free, sugar-free, Paleo, or something else?

- Step 2: Read the nutritional information. Once you’ve identified the “health halo” foods, take a closer look. Is your “healthy” organic dark chocolate peanut butter cup all that nutritionally different from that mass-market peanut butter cup? Chances are, it’s just different packaging.

- Step 3: Count how many varieties of junk foods you have. If you love ice cream—how many flavours do you have? If you peek into your cupboards, are there cookies, popcorn, sweets, or crisps? Without judgment, count the total junk food variety currently in your home. Generally, the more options you have, the easier it is to overeat.

The takeaway?

You’ll be more aware of the particular types of marketing you’re susceptible to, which you can use to make more informed food choices.

You’ll also have a better idea of which treat foods you prefer, and by reducing the variety of them in your home, you’ll cut down on opportunities to overeat.

3. Look for patterns.

We often use food for reasons other than physical nourishment.

For example, if we feel sad, we might reach for a biscuit to comfort ourselves. Temporarily, we feel better.

The next time we feel sad, we remember the temporary relief that biscuit brought us. So we repeat the ritual. If we continue to repeat this cycle, we may find our arm reaching for the biscuit tin every time we feel blue. We’re not even thinking about it at this point; it’s just habit.

Habits are powerful, for better or for worse. They can work for us or against us.

Luckily, we have control over this.

All it takes is a little time and an understanding of how habits get formed.

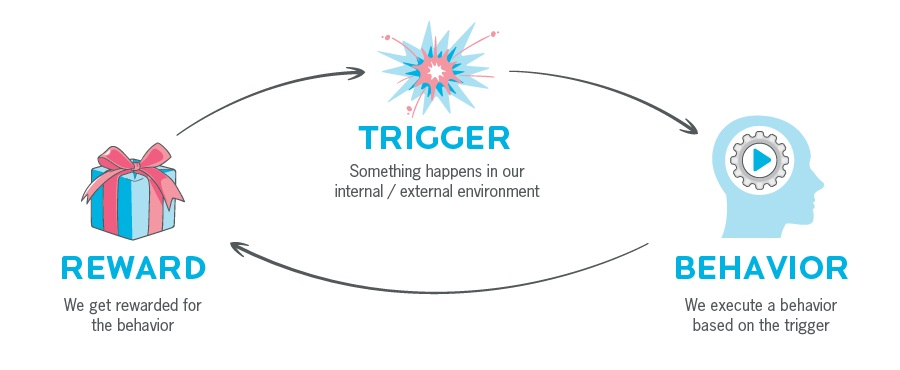

All animals learn habits in the following way:

This leads us to our next experiment…

Experiment #3: Put the science of habits to work.

If you want to break the habit of overeating, you can use this trigger, behavior, and reward loop to your advantage. Here’s how.

Step 1: identify your triggers.

A trigger can be a:

- Feeling. We might eat more when we’re stressed, lonely, or bored. Food fills the void.

- Time of day. We always have a caramel latte at 11am, or a biscuit at 3pm. It’s just part of our routine.

- Social setting. Hey, everyone else is having beer and chicken wings, so might as well join the happy hour!

- Place. For some reason, a dark movie theatre or our parents’ kitchen might make us want to munch.

- Thought pattern. Thinking “I deserve this” or “Life is too hard to chew kale” might steer us toward the take-away places.

When you find yourself eating when you’re not physically hungry, increase your awareness of your triggers by asking yourself:

What am I feeling?

What time is it?

Who am I with?

Where am I?

What thoughts am I having?

Keep a journal and look for patterns.

And remember: Overeating is generally problematic when it’s chronic—those pants are feeling pretty tight after most meals—or when episodes of overeating are particularly intense, like during a binge. So don’t get too worried with isolated episodes of overeating.To differentiate overeating from binge eating, keep in mind that binge eating feels disassociated, out of control, hard to stop, and usually comes with feelings of shame and guilt.

If, in observing your eating patterns, you discover that you may be dealing with compulsive bingeing behavior, then recruiting a doctor, therapist, or other qualified practitioner to help you navigate your feelings around food is likely the best course of action.

Step 2: Find a new behavior in response to your trigger(s).

Once you’ve identified your triggers, try associating new behaviours with them. These should support your health goals and feel good. If the new behaviours aren’t rewarding, they won’t be repeated, so they won’t be learned as habits.

In order to find the “right” new behaviour, it’s helpful to know that when we eat, we’re trying to meet a “need.”

So when you brainstorm new behaviors, find something that meets that need—be it time in nature, some human connection, a physical release, or just a break from your thoughts.

For example, I had a client whose trigger was talking to her ex-husband. She felt angry when she interacted with him, and some furious crunching on crisps temporarily made her feel better.

She eventually replaced the crunching with a punching bag session or by stomping up and down the stairs. Both activities were effective at relieving tension, but unlike the crisps, they supported her goals.

Step 3: Practice.

Every time a trigger pops up that compels you to eat, replace eating with a healthy feel-good behaviour.

Repeat this loop until the new behavior becomes a habit that’s just as automatic as reaching for the jar of peanut butter used to be.

Let’s take an even deeper look

Not all “feel-good” habits are created equal, in terms of their physiological effect on the stress response.

According to the American Psychological Association, the most effective stress relievers are:

– exercising / playing sports,

– reading,

– listening to music,

– praying / attending a religious service,

– spending time with friends / family,

– getting a massage,

– walking outside,

– meditation,

– yoga, and

– engaging in a creative hobby.

The least effective stress relievers are: gambling, shopping, smoking, eating, drinking, playing video games, surfing the internet, and watching TV / movies for more than two hours.

Although we may use the second list as “stress-relievers”—because they feel so good in the short term—they don’t actually reduce stress effectively.

This is because these habits rely on dopamine to give us a “hit” of pleasure. Dopamine feels rewarding immediately, but because it’s an excitatory neurotransmitter, it actually stimulates adrenaline and initiates the stress response.

In contrast, the first list of habits boost neurotransmitters like serotonin, GABA, and oxytocin, which calm down the stress response and induce a feeling of wellbeing.

Although these activities aren’t initially as “exciting” as the second list, they’re ultimately more rewarding and more effective at relieving stress long-term.

It’s not just about the food

As a dietician, I know how important nutrition is. So it might surprise you to hear me say the following:

It’s not all about the food.

Structure your diet around colorful, nutrient-dense whole foods, but also remember that a healthy life is not about calorie math or obsessing over everything you put in your mouth.

A healthy life is about giving time and attention to our whole selves.

Eating happens in context.

Pay attention to your mindset, your relationships, your work, and your environment.

When we’re well-nourished in other areas of our life, we’re less likely to use food as a cure-all when we struggle.

So if there’s one more piece of nutrition advice I have, it’s this:

Be good to yourself.

Not just at the table, but in all areas of life.

What to do next

1. Be kind, curious, and honest.

When we fall short of our ideals, we think that beating ourselves up is the fastest way to improvement. But it’s not.

Criticism and crash dieting may work in the short term, but can damage our mental and physical health in the long term.

Because overeating is already a painful experience, as you consider how these behaviors show up in your life and how you might address them, please be:

Kind: Be friendly and self-compassionate; work with yourself instead of against yourself.

Curious: Explore your habits with openness and interest. Be like a scientist looking at data rather than a criminal investigator looking to blame and punish.

Honest: Look at your reality. How are you behaving day-to-day around food? The more accurate you are at perceiving yourself, the better you can support yourself to change.

With this attitude of support and non-judgment, you’re more likely to move forward.

2. Use the “traffic light” system.

At Precision Nutrition, we have a great tool for creating awareness around food that I use all the time with my clients. It’s called the “traffic light” system.

You see, we all have red light foods, yellow light foods, and green light foods.

Red means stop.

Red foods are a “no-go.” Either because they don’t help you achieve your goals, you have trouble eating them in reasonable amounts, or they plain old make you feel gross.

Often, red light foods are processed foods like crisps, sweets, ice cream, and pastries. Red foods can also be foods that you’re allergic / intolerant to.

Yellow means proceed with caution.

Yellow light foods are sometimes OK, sometimes not. Maybe you can eat a little bit without feeling ill, or you can eat them sanely at a restaurant with others but not at home alone, or you can have them as an occasional treat.

Yellow light foods might include things like bread, pasta, flavoured yogurt, granola bars, or seasoned nuts. They’re not the worst choices, but they’re not the most nutritious either.

Green means go.

Green foods are a “go.” You like eating them because they’re nutritious and make your body and mind feel good. You can eat them normally, slowly, and in reasonable amounts.

Green foods are usually whole foods like fruits and vegetables, lean animal proteins, beans and legumes, raw nuts and seeds, and whole grains.

Create your own red, yellow, and green light food lists.

Everyone’s list will be different! You might leave ice cream in the freezer untouched for months, whereas another person might need a restraining order from that rocky road caramel swirl.

Once you have your list, stock your kitchen with as many green light foods as possible. Choose the yellow foods you allow in your house wisely. And red foods are to be limited or eliminated entirely.

At the very least, consider reducing the variety of red light or treat foods.

Take some pressure off your willpower and surround yourself with foods that support your goals.

3. Put quality above quantity.

It’s tempting to buy that jumbo bag of crisps because it’s such a good deal.

But remember: Real value isn’t about price or quantity so much as it is about quality.

Quality foods are nutrient-dense and minimally-processed. They are foods that you like, and make sense for your schedule and budget.

Quality foods may take a little more preparation and be a little more expensive up-front, but in the long run, they’re the real deal, and have a lower “health tax” to pay later in life.

4. Focus on whole foods.

Whole foods will make it easier to regulate food intake and will also improve nutrition.

We can almost feel “high” when we eat processed foods. Whole foods, on the other hand, are more subtle in flavour and require a bit more effort to chew and digest. Instead of feeling high, whole foods just make us feel nourished and content.

Whole foods are generally more perishable than processed foods, so this will require some more planning and preparation. So schedule some extra time in the kitchen—even ten minutes a day counts!

In ten minutes, you can cut up some veggies, boil some eggs, cook some oatmeal, or marinate some chicken breasts to make the following day go smoother.

While this might sound like more work, it’s rewarding. A closer relationship with food often means more respect and care for it too.

5. Find feel-good habits that support your goals.

Make a list of activities that you feel good doing. You might find that you like certain activities better than others depending on your feelings, the time of day, or your environment.

When you feel triggered to eat when you’re not physically hungry, choose an activity from your list.

This could be some gentle physical activity, fresh air, social interaction, playing a game, or a self-care ritual like painting your nails or getting a scalp massage.

The point is simply to disrupt the cycle of trigger > eat > reward, and replace eating with an activity that supports your goals.

6. Slow down.

If nothing else works, and the idea of taking away treat foods totally freaks you out, just do this:

Slow down.

Allow yourself to eat whatever you want, just eat slowly and mindfully.

Slowing down allows us to savor our food, making us satisfied with less. It also lets physical sensations of fullness to catch up, so we know when we’ve had enough.

Bingeing can feel stressful and out of control—by slowing down, we help ourselves calm down and take back some of the control.

7. If you feel like you’re in over your head, ask for help.

Sometimes we need support.

If overeating is especially frequent or extreme, or if you have health problems related to overeating that you don’t know how to manage, seek the help of a coach, nutritionist, dietician, or counselor who specializes in disordered eating behaviors.

There’s no shame in receiving support. The best coaches and practitioners often have their own support team too.

(This article was written and provided by Precision Nutrition – the world’s leading nutrition coaching educator and software provider. Author: Jennifer Broxterman, MS, RD)

BACK TO INFO HUBWould you like some help to become the healthiest version of you?

Most people know that regular movement, eating well, sleep and stress management are important, yet many need help applying this knowledge in the context of busy and sometimes stressful lives.

That’s why we now offer nutrition based services at Club Towers, available to members and non-members. Using the proven curriculum & resources of Precision Nutrition (PN) and delivered by our in-house PN Level-2 Certified Coach, our goal is to help our members and the wider community to achieve sustainable vitality through healthy nutrition and lifestyle habits…….whatever challenges you may be dealing with.

This is offered in three ways, a habit-based nutrition & lifestyle coaching programme, 1-1 consultation sessions and Information Hub.

To find out more about how we can help you, book a 20-minute consultation (free for all members) with our Coach, Ann Towers at [email protected].